A Museum of Natural Wonders: Betty Reid Soskin

The National Park Service was established in 1916, and just five years later, Betty Reid Soskin was born. It would take 85 trailblazing years for this force of nature to arrive at her park, but when Betty was made an official ranger at Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park, she breathed life into it, restoring a wealth of shared American experience that might have otherwise been lost. She recalls visiting only three or four National Parks in her lifetime, including The Grand Canyon, which she refers to as “the grand dame and most beautiful of them all,” but her favorite is the one she suits up for in the morning, the one she calls home.

Betty came to the National Park Service as a field representative of the California State Assembly, consulting for Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park at a time when “it didn’t know what it was to be,” she told us in a video interview. “It had a very limited life, a kind of bumper sticker life — ‘we can do it.’ I was able to help it become what it wound up being.” If not for Betty, Rosie may have been reduced to a bumper sticker. Betty became foundational to getting the story straight. “So many people have lived my history, and so many people have lived your history, and the nation is bereft without those,” she tells park visitors in the documentary No Time to Waste. “What gets remembered depends on who’s in the room remembering.”

For Betty, this meant remembering that her participation in the civilian effort to build what President Franklin Roosevelt called “The Arsenal of Democracy” occurred alongside the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans and the fatal explosions at Port Chicago. As a ranger at Rosie the Riveter, Betty invites visitors to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. “Somebody put a uniform on the life that I was already living,” she explained. “I was active on the home front, but I had completely forgotten it after the war ended, and here was a second time to be able to relive those years. As I lived them, they became alive for me, and I began to be able to share that. There were so many stories that had been forgotten; I was able to bring them back to life. That was something that I hadn’t expected, nor did the people. They were able to relive the stories through me, and that was an exceptional kind of thing to happen.”

After 14 years, she still finds her job to be exceptional, and when asked about her favorite part of it, she doesn’t miss a beat: “It’s the people,” the people whom she lovingly and jokingly refers to as “her public.” This reference is not at all inaccurate. Over the years, Betty has become a national treasure, a living legend in her own right. She’s given countless interviews to major media outlets, authored the acclaimed Sign My Name to Freedom: A Memoir of a Pioneering Life, and in addition to the aforementioned documentary, a new film on her life is slated for 2021.

“As I warmed up to being a ranger, my role with people began to consume my life. I was suddenly someone that I wasn’t sure I had known. Finding myself getting deeper and deeper into that ranger person began to be the payoff for me.”

There is a light in her eyes as she says, “Reliving a period of my life that I could not have known that I was going to live through was a gift that I don’t think I could have anticipated. But it turned out to be one of the most important things that I’ve ever been able to do.” She smiles: “I don’t know whether the government knows that it’s doing that when it’s happening.”

While we didn’t conduct a proper survey, it would seem that the National Park Service does hope to create such experiences. Megan Springate, who works at the National Park Service (NPS) Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education in Washington, D.C., writes on nationalparks.org:

“There are parks across the country that preserve and celebrate incredible landscapes and the plants and animals that live there. And there are parks across the country that preserve and commemorate pieces of our national history that could otherwise vanish… With over 400 sites and programs that reach into every county across the country, we have a responsibility to do good history.”

Betty is integral to fulfilling that responsibility and has received widespread recognition for her service, perhaps most notably by President Barack Obama who presented her with a commemorative presidential coin.

She glowingly recounts the story. Imagine, “meeting the president and his wife and introducing him to the nation on television, knowing that we were standing on the stage, within sight of a slave-built capital. I have a picture of my great-grandmother [who was born into slavery] in my breast pocket, and I’m speaking to the person who is now the president of the United States, for the first time. And the wonder of that washes over me constantly. I have to remind myself that I’m really Betty.”

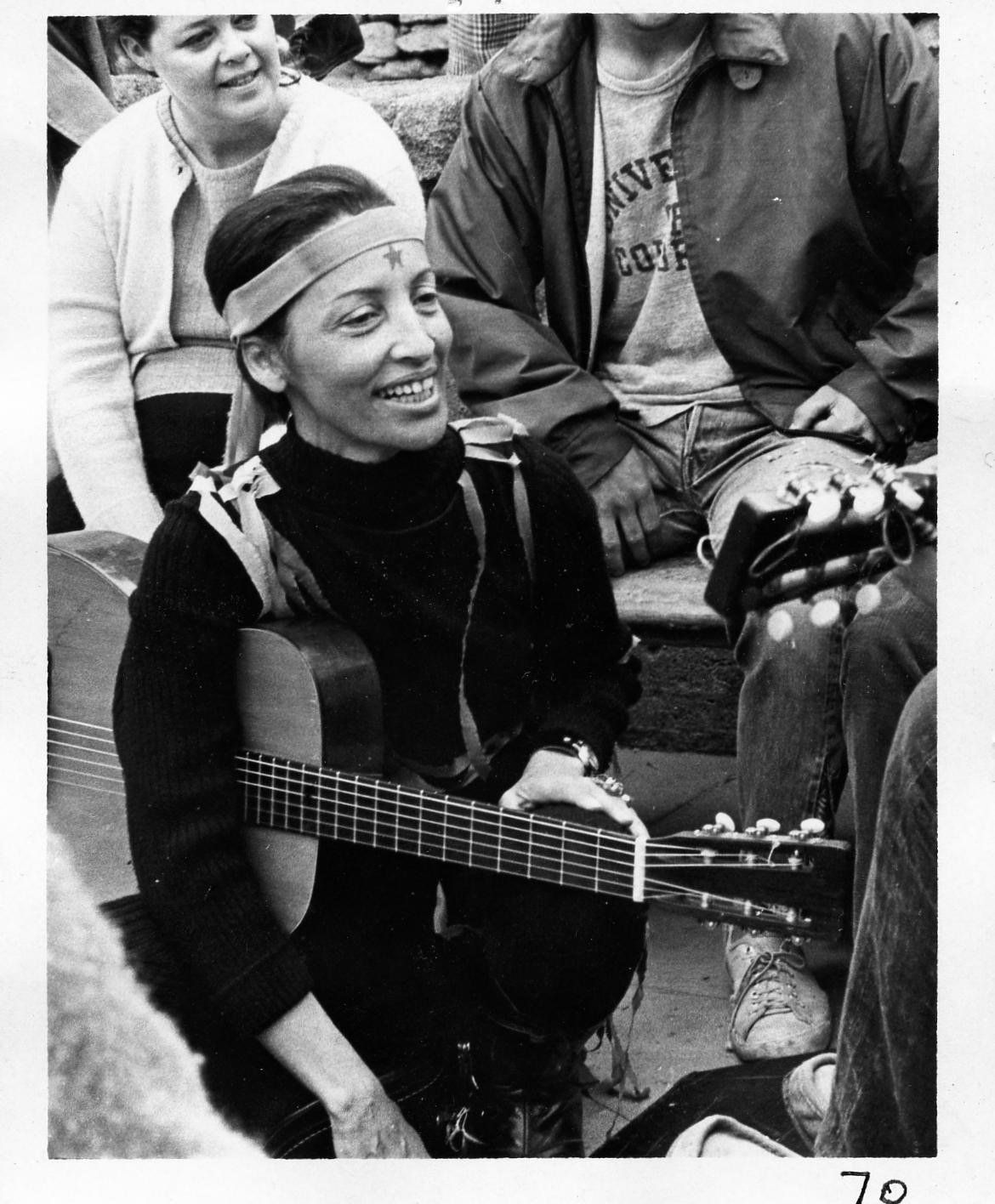

Being Betty, wonder is a theme. When asked what makes her feel alive, she looks up, searching for the words. “Oh, there’s so much.” But it hasn’t all been wondrous. “My life was mixed with beauty, with sadness, with struggle, with more things than anyone needs to have.” She recalls a period in the 1950s when she and her husband Mel Reid were living in a wealthy Oakland suburb, a suburb full of white people trying to prevent people who looked like Betty from moving into their neighborhood. “I was living a life of rejection. I began to be able to process all of that by writing music. My husband had given me a guitar. I had taught myself to play. Now, when I go back and sing those songs, they are so much a part of life as I knew it then.”

It’s as if the songs are artifacts in the living breathing museum of natural wonder that is Betty Reid Soskin. “They are so much me, that I wonder what there is that allows us to find what we need to find within ourselves. Because I found it. I didn’t ever accomplish anything out of what I did with music. I didn’t ever copyright anything, or publish anything. I buried them in the back of a closet in an old shoebox, and only recently have they been rediscovered. Now they’re becoming the soundtrack for a film, and I’m finding them beautiful. I sang one of them with the Oakland Symphony recently. It was astounding. I was able to sing a song written way back. And it held up.”

When asked if she’s inclined to write more songs, she says, “No, that seems to have been a time when it was for me to do. I wrote them without expecting anything and it seems now, that they were written as a way to take care of my daughter, who is mentally retarded, after I’m gone. So, there is time. Now it seems that nothing is accidental. Everything has been timely. It’s all playing out accordingly. And I love that.”

Betty had four children. However, she finds it remarkable that her children don’t factor into her persona as a ranger, as she spent her time on the home front of the war before they were born and returned to tell the story well after they had grown.

She marvels at how such a huge part of her experience could remain unexplored. But with Betty, there’s still so much to discover, 99 years of bearing witness to incredible upheaval and transformation, a transformation that Betty finds to be in full effect today.

She offers words of wisdom for young people who are now witnessing what history might forget. “The need to record everything is so great. So many of us are moving through life so fast that we don’t really find the time. And it is not only the large things. It’s the many small things that make up the large things that become so important. It’s the smaller things in life that I now find so much in.”

She’s absolutely vibrant. “I came to terms with life when I realized that I was not going to ever be able to answer all the questions that I had. That it was the questions that I was going to die with. That I don’t know. And that maybe that’s the secret, maybe it’s not knowing. Maybe it’s that, that throws me into the future. And I love that. I’m not only satisfied with it, but it really seems to be the answer — that there is no answer. That we each are given a period of life to live, and that we live it. In the collective wisdom of all of us, as we are going through that life that has meaning, that that’s what is.”

If she had one word, it would be “why,” she tells us. “It’s important that the questions remain alive in everybody. We have to remember that we can’t know. That it’s a seeking; it’s trying to find out. It’s dying without knowing that keeps one alive. I think that that is what has kept me alive. I think my children will find it keeps them alive.”

In Betty Reid Soskin, we see that our National Parks are not only about preserving natural resources but about honoring the stories of our people, and the land that bears witness. We go to our National Parks to get lost in nature and to find ourselves, to remember where we came from and who we truly are. And as Betty reminds us, to live the questions that keep us alive.

This article originally appeared in

Garden & Health.