Blog

Blog

By Kate Tucker

•

November 7, 2023

West Virginia is a mythical place wildly misunderstood and often overlooked, chock full of natural resources and endless stunning vistas, despite having been ravaged by extractive industries and left to pick up the pieces of the energy transition in real-time. My family comes from West Virginia; from Sicily and Scotland, they settled in the hills of Appalachia, which may have looked a little like the Highlands, a little like Mount Etna. They came for the coal, or the promise of a gainful employment. My grandfather worked in the mines until he worked his way out of them, landing a more sustainable job driving truck. He died of cancer when he was 35. Although I never met him, I looked for him every summer in those misty mountains, winding our way back to Coalton with the windows down, my mom singing along to John Denver. Almost Heaven, West Virginia isn’t just coal mines and country roads. Called the Birthplace of Rivers, the state sits on the Eastern Continental Divide, where 40 rivers and 56,000 miles of streams provide drinking water for millions of people from the Chesapeake Bay out to the Gulf of Mexico.

By Kate Tucker

•

October 10, 2023

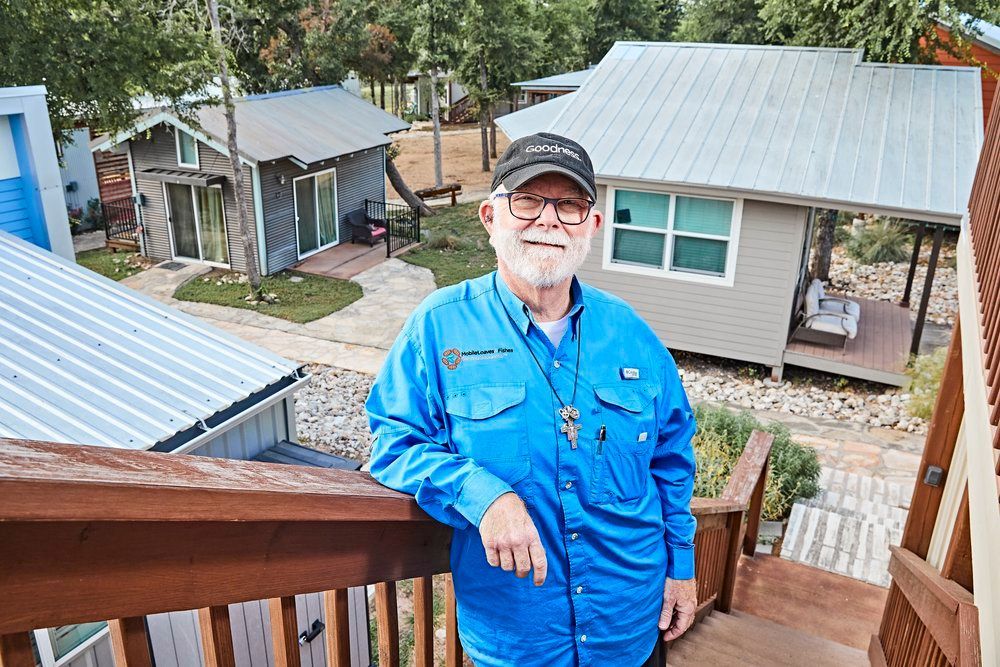

I met Alan Graham on the other side of a Google search for sustainable homes for the homeless. I had heard of communities working on innovative housing solutions, like Seattle where people are building tiny homes in their backyards with the help of groups like the The Block Project . But then I stumbled upon Community First! Villag e, an enclave of 400+ chronically homeless residents now living in permanent homes alongside neighbors and friends. I had so many questions. How do you even begin to develop a place like this? How do you manage the ever-evolving needs of a population accustomed to being underserved, disregarded, unwanted? How do you organize systems to support the only approach that could work, a full-scale holistic overhaul of what it means to serve the homeless, and to live in community with one another. Our understanding of homelessness in America varies based on geography, privilege, and personal experience. Even the way we talk about homelessness is fraught with preconceived notions and misconceptions. Do we call people “homeless,” or are they “unhoused?” How many times do we give cash to the guy on the corner before it makes a difference? Do we give him anything at all? If I stop and listen to this person in the parking lot, will they just spin me a story? Are they dangerous? Why are people in the richest country in the world living without shelter? Who is responsible for fixing this? Who decides? I asked all of these questions and then I met Shirley. I'm drinking coffee on a gray winter's morning in Nashville, and from my apartment window I can see the line of traffic on Hermitage Ave spilling into downtown. But today on the sidewalk, there’s a woman in a colorful dress with several bags slung over her shoulders. She’s bending down in the tiny space between the chain link fence and the sidewalk picking up something off the ground, over and over, like she’s harvesting flowers. But nothing grows there. More out of curiosity than generosity, metered with my usual social anxiety, I leave my apartment and cross the street with a cup of coffee and a muffin. I’m not sure if she’s homeless, and I don’t want to offend her, but nobody hangs out on that tiny stretch of sidewalk and it is breakfast time. I introduce myself and we get to talking. Her name is Shirley. She’s just a few years younger than me. She's on the run from a bad relationship in Georgia, but she's had to leave her kids behind and she needs to get them back. I offer to buy her breakfast at the diner next door and she declines, but we agree to meet the next day and talk some more. Oh, and she was collecting tiny leaves to make into paper. I am determined to get her some help. Surely in a town as resourced as Nashville, with a well-connected advocate, it will be simple enough. I start making calls. Nobody can take her in. She isn’t on drugs. She doesn’t have a disability. She isn’t mentally ill. She isn’t an addict. She isn’t a resident of Tennessee, and she might not be an American citizen. Her plan to start a business selling stationery, well that’s the best thing we’ve got. We come to this conclusion over breakfast at McDonalds inside Walmart where we're picking up toiletries and other basics. All her belongings are now temporarily stored in the trunk of my Honda Civic. She asks me to take her to a suburb outside of Nashville. She thinks she might have a lead there, someone who knows where her kids are. We drive for twenty minutes and stop at a library just off the interstate. I help her sign up for an email address. It requires a backup phone number and I enter mine. Is that dangerous? I wonder. Who knows. She struggles to log in on her own and I worry that my messages to her will just sit there, unread, locked behind a password neither of us can remember. And that is what appears to have happened. When we part ways that day she says, "I’ll be back in Nashville soon,” and I say, “Don’t forget to check your email, so we can find each other.” I do see her again, a few days later walking down Hermitage Ave, but I’m late for work and traffic is moving fast. I wave as I drive by, but she doesn’t see me. The next day I buy a cell phone, a pay-by-the-month deal. I want to give it to Shirley so she can call me, or call for help, or maybe even call her kids if she can get their number. I wait by my window but she doesn’t show up. I send email after email. I walk down by the river, under bridges, where people without houses build fires to cook dinner. She’s not there. Then, a huge storm hits Nashville. The river swells. They say a handful of people died down there, homeless people caught in the flood and the high winds. I have no way of knowing where Shirley is. Or if she is still alive. A month goes by and I cancel the cell phone. I hope and pray that she’s made it to Georgia and is living with her kids today. My first direct encounter with homelessness left me feeling helpless. And the helplessness I felt was nothing compared with what Shirley faced daily. I had considered inviting her to stay with me in my tiny studio apartment, but in talking with some friends in social services I was advised against it. I had no idea how hard it is to get up off the streets once you find yourself living there. In the United States, the odds that you or someone you know will end up homeless are as slim as 1 percent of 1 percent. But the chances that you will move from chronic homelessness to a permanently housed situation can seem just as dire.

By Kate Tucker

•

October 3, 2023

Food. Everybody needs it , not everybody gets it in the same ways at the same levels of freshness and nutrition. And with human population projected to reach over 9 billion by 2050 , how are we gonna grow all that food? To kick off this season of the HOPE Is My Middle Name podcast we’re looking at food, how we get it, how we grow it, and how our biggest challenges might require smaller solutions. And since I’ve been spending a lot of time with farmers across America, I figured there was one out there who could show us a thing or two about the BIG the impact of small farmers.

By Kate Tucker

•

December 13, 2022

The National Park Service was established in 1916, and just five years later, Betty Reid Soskin was born. It would take 85 trailblazing years for this force of nature to arrive at her park, but when Betty was made an official ranger at Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park, she breathed life into it, restoring a wealth of shared American experience that might have otherwise been lost. She recalls visiting only three or four National Parks in her lifetime, including The Grand Canyon, which she refers to as “the grand dame and most beautiful of them all,” but her favorite is the one she suits up for in the morning, the one she calls home. Betty came to the National Park Service as a field representative of the California State Assembly, consulting for Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park at a time when “it didn’t know what it was to be,” she told us in a video interview. “It had a very limited life, a kind of bumper sticker life — ‘we can do it.’ I was able to help it become what it wound up being.” If not for Betty, Rosie may have been reduced to a bumper sticker. Betty became foundational to getting the story straight. “So many people have lived my history, and so many people have lived your history, and the nation is bereft without those,” she tells park visitors in the documentary No Time to Waste. “What gets remembered depends on who’s in the room remembering.” For Betty, this meant remembering that her participation in the civilian effort to build what President Franklin Roosevelt called “The Arsenal of Democracy” occurred alongside the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans and the fatal explosions at Port Chicago. As a ranger at Rosie the Riveter, Betty invites visitors to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. “Somebody put a uniform on the life that I was already living,” she explained. “I was active on the home front, but I had completely forgotten it after the war ended, and here was a second time to be able to relive those years. As I lived them, they became alive for me, and I began to be able to share that. There were so many stories that had been forgotten; I was able to bring them back to life. That was something that I hadn’t expected, nor did the people. They were able to relive the stories through me, and that was an exceptional kind of thing to happen.”

By Kate Tucker

•

December 6, 2022

In the age of TikTok and Instagram, it seems there’s no place we haven’t seen, but if you’ve ever been to Alaska, you know there’s a whole lotta world left to discover — a world on the forefront of climate change, the energy transition, advocacy for Native rights, and — regenerative tourism. Because amid the challenges Alaskans are navigating, including transportation, supply chain, and food security, they’re seeing unprecedented numbers of tourists. Cruise ships cause the islanded town of Sitka to swell from under 9,000 to nearly half a million people in the summertime. These ships bring opportunities, and they also bring complications for the people who live there, and for the environment. As a regenerative tourism catalyst, Mary Goddard relies on Alaska Native values of sustainability and hospitality to help build a healthy relationship between her community and tourists who visit. Mary tells us: “When you talk about regenerative tourism, it's always based on indigenous knowledge and wisdom, and you can see that across the world. Where you're from, you are an ambassador for your place. You see yourself as a steward of the land and the ocean and the culture and your community.”

By Kate Tucker

•

June 7, 2022

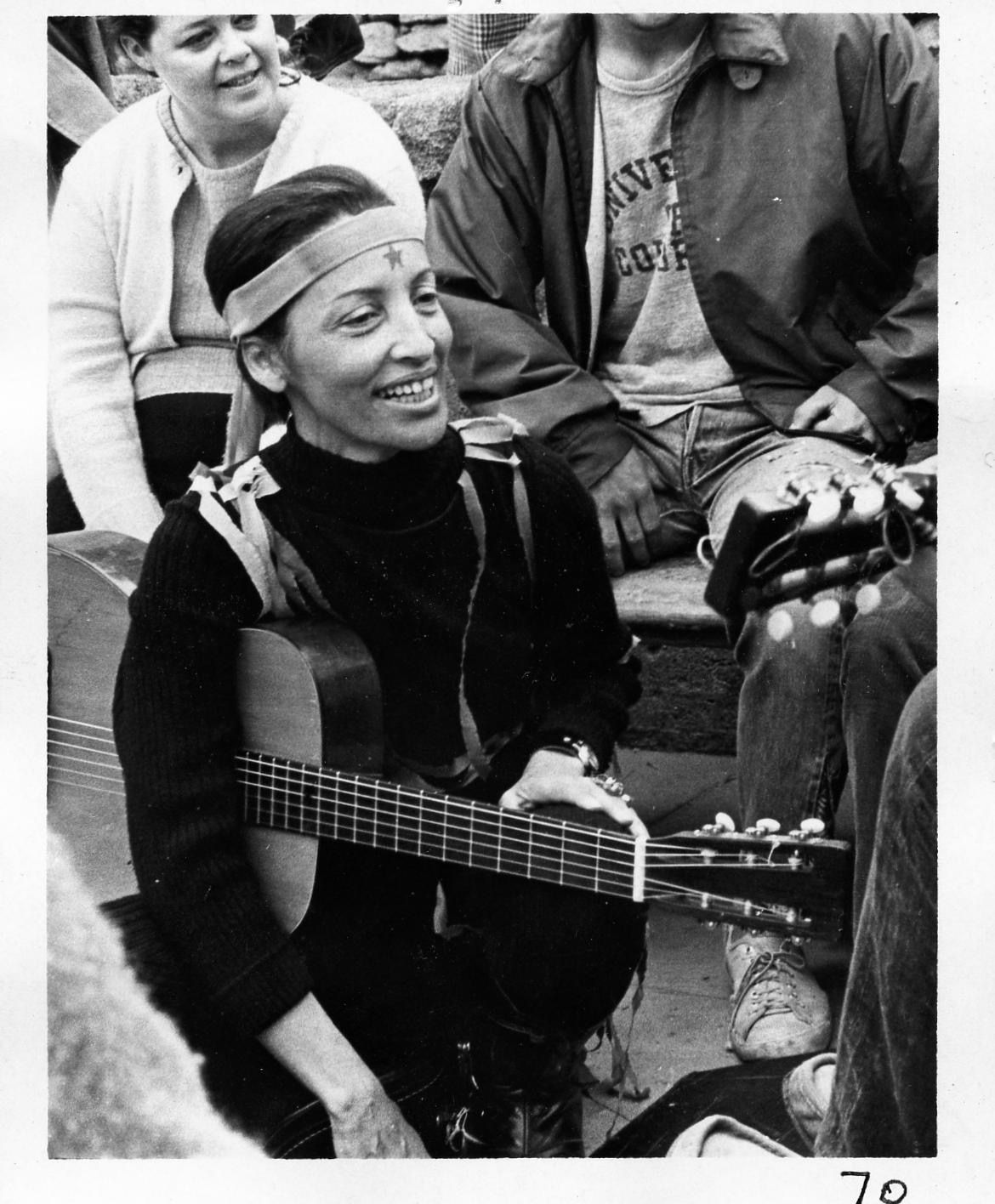

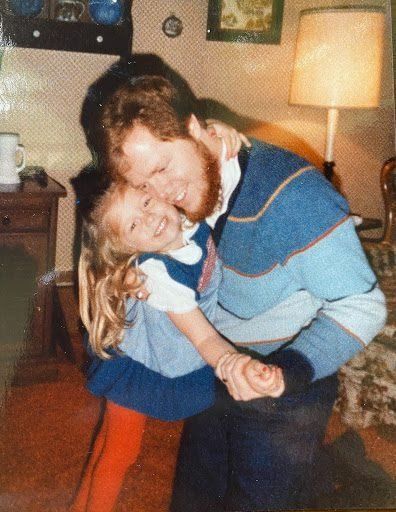

We recently released the new podcast called Hope Is My Middle Name , where I get to interview people doing big daring things to make the world better, people who give me reasons to hope. Hope is something I’ve been thinking about for as long as I can remember, partly because Hope is my middle name. So before we launched the podcast, I called my dad to ask him how I came to have that name, hoping to understand a little more about this lifelong quest for hope.

By Kate Tucker

•

June 17, 2021

On a gentle hill on the outskirts of Bristol, Vermont there lies ten acres of rich farmland, rolling fields of perfectly plotted perennials– trees, nuts and berries — mushrooms to fertilize the orchards, chickens paying their rent in eggs, and goats to cut the grass. Rows of saplings line the perimeter, smartly controlling soil health and erosion. From oaks to elderberries, each tree has a specific purpose, whether for food, windbreak, firewood or forage. Every element of the farm is mission-driven and artfully engineered by an equally complex and vibrant ecosystem within the mind of Jon Turner. Retired U.S. Marine, Iraq War veteran, young father and now homesteading farmer, Turner, with his wife Cathy, started Wild Roots Farm five years ago with the goal of healing himself from the scars of a war-torn service, along with other veterans who would make a pilgrimage to the farm, and ultimately, the land, through the practice of sustainable agriculture. Wild Roots Farm now produces enough food for the Turner family, with plenty extra to give back to the community. If 15 years ago, you had told Jon Turner he’d be farming the land and leading hundreds of students, veterans and community members in the same life-giving practices, he wouldn’t have believed you. Between 2004 and 2007, Turner served three tours, one in Haiti and two in Iraq. On his final deployment to Ramadi, he nearly died when a mortar blast sent shrapnel into his jaw, narrowly avoiding his carotid artery. Suffering a traumatic brain injury, he returned home with severe PTSD.

By Kate Tucker

•

June 3, 2021

Brittany and Brian spent one sweet and loving year of marriage before Brian suffered a heart-attack and left Brittany a widow at age 28. It was an unimaginable loss. Brian had been healthy, active and full of life, the thought of a fatal undiagnosed condition seemed impossible. Last year, Brittany bravely documented her journey through grief to a deeper sense of faith as she did what she and Brian loved to do together — she went hiking. And she really went for it. She quit her job and set out alone on the Appalachian Trail. In a two-part conversation, Brittany shares her experience hiking through the valley of the shadow of death.